When you look for it, Japan seems rife with “ninja experience” programs and attractions that merely belabour what it truly meant to be a ninja during the country’s warring eras. Those who have researched ninja and ninpo know that ninja are not the mystical beings media and the entertainment industry has made them out to be.

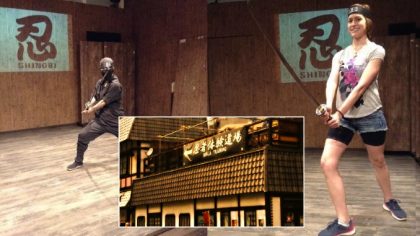

However, throughout the world—Japan included—there are groups who cater to the fictional images of ninja, and then there’s those who seek to inform the masses of the truth. Fortunately, a true ninja clan, Musashi is the latter, and so my experience at the Musashi Ninja Clan’s Jidai Dojo taught me more about the ninja than I’d expected.

History of the Musashi Clan

Prior to talking about the experience, I think it’s necessary to assert that the Musashi clan is as authentic as the Iga are. The group has survived since Tokugawa Ieyasu ruled the country. An intense history unfolded from the moment that leaders, the Shibata family, became retainers to the shogun.

We can assume that before the Shibata family relocated to Edo with Tokugawa in 1590 that they had been studying ninjutsu prior to that. Mentioned in the family’s biography is that that third generation beneath Tokugawa rule were granted roles outside of jounin and chuunin. That is, they were raised to levels of higher executive status, such as magistrate. The fact that the Shibata family held both samurai and ninja status was extremely rare.

Hanzo Hattori is one of the few to also have been placed in this important position. However, where the third generation Hanzo laid down his weapons to build a temple, the Shibata clan performed their duties devoutly until the late 1800s.

Shibata Sadataro – Emisary for Japan (under the Shogunate)

Around 1860, Shibata Sadataro Takenaka was the commissioner of foreign affairs for the Tokugawa shogunate. The diplomatic role afforded him the ability to create peace between nations. He also played a role in espionage while traveling abroad.

For example, Shibata Sadataro and his relative, Nakagawa Tadamichi, the then Lord of Bicchu, went to Paris to meet with Napoleon III in 1867. When he returned to Japan, he was made the magistrate of Osaka and Kobe and worked fervently with his 12 onmitsu to keep Japan’s ports open to allied nations.

The Tokugawa shogunate collapsed in 1868, but the Meiji government approached Sadataro for work. Though all good lives must end, Sadataro’s will for peace lived on through his family. The Shibata clan upheld leadership over the shinobi in Tokyo until about 80 years ago, when the grandfather of the current Shibata clan leader decided to leave the ninja way of life to be an officer for the Salvation Army. Because of the great amount of volatile information the Shibata clan had dealt with for hundreds of years, the family decided to keep quiet about their ancestry for some time.

Present Representative of the Musashi Clan

(Image from Vanessa’s Facebook page)

However, the family continued to teach their unique form of martial arts. The present weaponsmith of the clan trained under Kenpu Matsuo, the founder of Kuroda-ryu Ninjutsu. Many of the weapons on display and for use in the dojo were handcrafted by the Shibata clan weapon master. Many are also on sale.

So why did the current Musashi clan decide to start reaching out to the masses? What made the 18th generation clan leader, an amazing woman named Shibata Kiyomi Vanessa (also known as the ninja Suzak), take this route? Like many of us, she was completely in the dark about the ninja activities of her family for a long while.

She wanted to keep up the legacy of fabricating international friendships and bring to light the true nature of ninja.

I’d say she’s doing an amazing job.

The Program – Certification Training (120 minutes)

Because I was gung-ho and wanted to get the most immersive experience possible, I chose the longer of the two programs—either 90- or 120-minutes—offered at the dojo. The 120 minute program is also called the “certification” route. A rough outline of how the course runs is also follows:

- Opening meditation

- Enbu dedication to the Musashi clan ancestors

- Change into the ninja outfit

- Weaponry and tool introduction

- Movement practice

- Stealth practice

- Sword practice

- Ninja star throwing

- Blowgun practice

- Meditation

- Kujikiri (Well-wishing)

Do note that the group offers interpreters if you don’t understand Japanese. However, because I’m fluent in Japanese, it was very much a private lesson. Since my ninja instructor didn’t have to take extra time waiting for interpretations, we delved a bit deeper into several of the listed sections.

The opening meditation is purely a show of respect set in a dark room—the traditional atmosphere of ninja houses. Once you bow and exchange greetings with the ninja instructor, you will be lead upstairs for raiment fitting. Here I learned something new. According to my instructor, male shinobi would cover their faces, but kunoichi, on the other hand, rarely did so.

You are invited to look around at the small shop where weapons, historical photographs and various souvenirs are on display. It was at this time that we conversed about the history of the Shibata clan.

The Tools and Weapons

Westerners have an image in our minds that shinobi were supernatural assassins or the stylized video game reincarnations of Hanzo Hattori. Recent exhibitions like “Ninja: Who Were They?” at Japan’s Miraikan museum are opting to inform the masses that ninja were not what media has made them out to be. When the Musashi ninja instructor pulled out a veritable toy box of ninja tools, he firmly stated that while most of the items look like weapons, they originally had other purposes.

Of course, one thing the ninja were masters of was multi-tasking and creativity. We talked at length about how certain tools have been used exclusively as weapons in anime and movie adaptations.

Take the kunai blade, for example. Anime like Naruto will lead someone to believe that kunai is a knife. My instructor, though, explained that this was not the real intention.

It’s a shovel. Carving, climbing, inscribing, lock-picking, digging and cooking were the main uses of the kunai. Not stabbing.

I was handed several tools that looked like they would cause serious pain but had other uses. The weapons featured a kokeshi doll with a head that popped off to reveal a poison-soaked needle, a weighted chain that mimicked prayer beads, caltrops, shuriken and a short scythe.

The element of surprise

Because ninja were not solely employed to infiltrate manors but to spy on enemy villages, map out unknown towns prior to invasion or communicate messages to other onmitsu nearby, they only carried what was suitable for the mission. So if they were walking down a road in the daytime, their hands would be in their sleeves, holding onto a handful of caltrops or two shuriken. Should they be discovered, they would rarely engage their foe. Rather, a ninja would throw hindrances then flee.

The element of surprise was a ninja’s ultimate weapon.

Disguise was another method of gathering information. Women excelled at this better than the men, but both genders engaged in “performances” and other jobs, like acting as a monk on pilgrimage, to blend in with the surroundings while simultaneously garnering as much information as possible. So when other research evidence has proven that ninjas were originally mountain monks and wanderers, I would say this cements that proof. Even the Shibata family operated in careers outside of direct espionage for over 200 years.

The Base (of Movement)

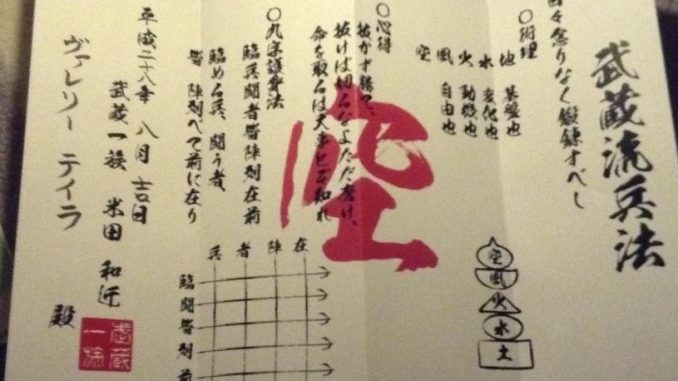

With the basics of ninja tools covered, and the purpose of ninja discussed, we moved onto the “base”, written as 土 on the chart of the components to the training. The others are 水 (water)、火 (fire)、風 (wind)、and 空 (emptiness).

The “base” refers to the body’s connectedness to the earth. In the past, before the German military training found root in Japan, the way Japanese walked was different. So how did Edo period warriors stand?

- Feet apart, toes turned slightly outward

- Knees slightly bent

- Hands resting at the crease between the hips and thigh

- Spine long, chest open

- Shoulders back and down

This groundedness was surprisingly pleasant. It’s amazing how well you can breathe when the body is centered, the feet are connected to the earth, and your spine is lengthened. Completely opposite to how most people move, all slouched over their phones. Even during movement, this crouched position made for quick, energetic movement that didn’t tire the body. Some of this had been touched on at Miraikan, but now to experience the effectiveness meant increasing my understanding.

I’m sold, honestly. I might start walking around like a ninja more often. Stepping, too, became airy and quiet. Everything moves beneath your center. You switch feet, swivel the torso to the side, and keep both knees bent. The sideways stance of the torso paired with wide feet means the ability to absorb shock.

The silent & defensive nature of movement

The instructor even gave me a light tackle to essay just how well these movements acted defensively. “From the front,” he said, “humans are relatively weak.” To prove this, he sent my backwards with a poke. Sideways, though, was a different story.

Since I had down the basic steps, Sensei introduced jumping. The hurdle was small, so getting over it was no issue. Doing it silently was the goal.

“Written in many ninja texts is to watch animals and learn of their movements,” Sensei told me. “An example would be when ninja would learn how to bark like a dog to dissuade security guards from getting too close to where a ninja was hiding.” On that note, it was explained that ninjas were interested in how cat’s leap.

Thus did I come to understand how to move like a ninja and land on the balls of my feet noiselessly. I was even challenged with twists and going for it at a run.

The Flow (of a Sword)

The water symbol is affiliated with learning how to move endlessly through action. To demonstrate the meaning of this training module, I was handed a wooden sword. Having participated in kendo previously, I knew what the instructor was talking about and how to do the footwork from the beginning. Though swordplay can be broken down in waza, or single movement, a true master moves through each motion fluidly. Each step is matched with the purposeful motion.

We went through the reasons for hand placement, where to aim the blade at the enemy, and how to react when the adversary would feint. I think Sensei was testing me at this point. Some of his feints were fast, and it took a lot of willpower to the flinch at the wooden blade coming straight at my throat. Of course, this is part of the training: how calm and collected can you be to bring the blade back to the center?

Then we broken down the waza. Step-by-step, slice-by-slice. Where was the blade supposed to cut? What was the meaning behind each stance?

Experiencing the samurai mindset

I knew that samurai and ninja believe in being able to communicate their emotions when crossing blades, but this experience definitely gave me unique insight. Though following Sensei’s instructions, I went through the waza, parrying and countering, staring into his eyes, and sensed a glimmer of what would be going through a true warrior’s mind.

The instructor told it like this: Every crossing of blades asks a question. Why are you attacking me? What are you feeling? Are there others nearby? Is anyone in danger?

And so the flow of the sword is not just the movement, it is the link you have to the world around you. Like water, you move with the energy of the universe, use the stream of stimuli to gain information, and maintain a flow of communication with both allies and enemies.

The Fires (of Chance)

People are not usually risk-takers. People panic. Unless you are connected to your mind and body, there are certain things that happen when working as a ninja that cause serious moments of terror. Naturally, the Jidai Academy’s experience doesn’t aim to give you PTSD, so they make this reaction training as fun as possible.

That’s when shuriken throwing came into play. Stars and needles were introduced as the eptiome of “chance.” You need a good amount of reaction time to not only throw the stars, which maxed out at two on hand during any given mission, but to hit the target and keep moving.

For whatever reason I’m pretty good at throwing stars. I learned that back at the Hanayashiki experience. So Sensei decided to becoming a moving target in a roleplay scenario. I had to hit him once with an overhead throw, switch footing, then do a throw from the hip. Once he moved behind revolving door, I needed to collect my shuriken then escape before he returned with his sword.

Throwing Shuriken

The first few times when Sensei behaved more like a cardboard cutout were easiest. Afterwards, he ramped up the challenge by climbing the walls, leaping, and bringing a sword.

I managed to hit him almost every time, but then he met my gaze and lifted his sword. My heart stopped. Though I was only throwing rubber, the thought went through my head, “But what if I hurt him?”

This emotion was explained afterwards as the “fire,” the “chance” that all ninja trained themselves to take regardless of what instinct demanded that you do.

Throwing Chopsticks

I was also allowed to try something fun. Because my shuriken-throwing skills were decent, Sensei handed me chopsticks. Yes, the ones you eat with. He told me with a laugh that chopsticks aren’t normal ninja weapons because of how light they are. The technique for throwing needles is different the stars, more of a circular swipe of the hand that releases the needle at a certain point in the air for gravity to take over. Chopsticks required even more speed to make them stick.

After a few throws, Sensei turned to me, bowed and said in English (though we’d be speaking in Japanese up until then), “I have nothing left to teach you.”

But Sensei! There’s more!

The Wind (of Freedom)

The last physical segment of the training had to do with the 風 kanji for “wind.” It was time for the blowgun. Starting from the basic standing position I’d learned in the earth segment, paired with a calm mind and easy breath, I had to take a chance and shoot a tiny dart at the bull’s eye. Then I had to flee for freedom. Free movement, free breath, and the goal to stay free is what revolved around the blowgun.

At this point I was given a mission. I needed to sneak in through a rotating trick panel—making sure not to leave it open—then do a cat jump over an obstacle, locate the dart, pop a ballon, hit the target, then escape before the guard could capture me. Easier said than done. I thought for sure I’d mess up somehow. I did everything quietly, shot the balloon, hit the bull’s eye then scurried out of sight before the instructor could catch me. Where did I fail? I forgot to close the door all the way.

So he stuck his sword through the gap and said, “I can see you! Shut the door!”

The Emptiness (of Oneself)

Zen Buddhism has no doubt influenced some of the philosophies behind ninjutsu. The final symbol of the training, 空, has two readings: sky and empty. Rather than thinking of empty being “devoid of things,” the idea behind this is to empty onself of fear, apprehension and other negative emotions. Though the Hanayashiki ninja dojo and the Miraikan exhibition had discussed this somewhat, the actual feeling of meditation had been left out.

I loved this part about Kujikiri. The Musashi clan has done a wonderful job of explaining why ninja used hand positions so extensively.

Kuji Kiri

First, I was introduced to the meaning behind the familiar “jutsu” pose seen below:

The left hand (on the top) is the scabbard of your sword, which is your right hand. Sensei explaining that when you hold the right hand in front of you as you would a sword, the line from your pointer and middle finger activates the muscles of your back. A fist, however, shortens the muscles and recruits the chest.

When drawing the 十 kanji in the air and saying:

- (臨) Rin

- (兵) Hyo/Pyo

- (闘) Toh

- (者) Sha

- (皆) Kai

- (陣) Jin

- (列) Retsu

- (在) Zai

- (前) Zen

You are actually making the grid-like roadways of Kyoto. On these roads, you cut through the darkness and uncertainty. Reading the symbols as their various meanings, a story unfolds that speaks of conquering your personal fears to take on whatever is in your way. Pretend that you stand amongst an army of thousands, and in doing so you will gain the power needed to survive. It’s written on the certificate too.

About the Instructor

The man that was charge of my lesson today was incredible. He wasn’t an actor or a detachment employee. No, he is a real-life ninja with years of martial arts and ninpo training. The essence of the shinobi philosophy—to care for community, to protect those who can’t protect themselves, to treat oneself with kindness—emanated from him.

I asked him how long he had been training in ninjutsu. For 8 years he’s worked as a director for the Musashi ninja clan. Beyond giving lessons at the dojo, he teaches martial arts and does various ninjutsu-related workshops throughout Japan. Having studied philosophy in college, he works to blend mind-and-body practices and aims to enlighten people to the healing benefits of a mindful lifestyle. I found this extremely inspiring.

Better yet, if you ever had any doubts about ninja training being less about physical strength and more about the mind, here’s proof. Sensei divulged that in high school and college he was big into MMA and had done years of Judo and Karate. However, he wore himself out with the constant aggression of these disciplines and sought something more restorative. Thus did he find himself learning Musashi-ryu, the style of the dojo. It helped him heal.

Final Thoughts

So if you want to be a modern day ninja, you don’t need a sword and poison-tipped darts. What you need is a grounded stance, verbal and non-verbal communication skills, the desire to never give up, and the will to be free. Seek to be of service, but remember to care for yourself as well. Seek balance but accept that there is no absolute balance. That is what the Musashi ninja clan aims to instill in you by the end of the program.

The training is not necessarily tiring, but it does make you think about ninja in another way. The extensive information you are offered about how ninja lived and moved is undoubtedly real, because you are receiving this knowledge from genuine shinobi. Explanations are informative, the physical challenges are fun and creative, and you are treated with the utmost respect by the entire group. Overall, I definitely recommend the Musashi Ninja Clan experience for anyone with a firm interest in what it means to be a ninja.

Access Jidai Academy Dojo in Tokyo

Jidai Academy Dojo

Address: Tokyo, Kita-ku, Tabata-shi 6-35

Phone: (+81) 90-3691-8165

Editor’s note:

This report uses the terms ninjutsu and ninja loosely, in a non-historical context. It regards the ninja training as a cultural travel experience, with a family whose history is linked to Tokugawa onmitsu (spies for the Tokugawa government during Edo period).

![5 Reasons Why You Should Train at the Birthplace of Muay Thai [Travel]](https://www.wayofninja.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/4419160179_5ab2a8415e_b-420x185.jpg)